the machine to live

HERE IS a version of a famous aphorism that will be forever associated with Le Corbusier: the house is a machine in which to live. He spoke it in the nineteen twenties, a time of the socialist experiment, the great aftershock, the explosion of the avant-garde, and later he died, as we all will, leaving us to think of what he meant.

What is the machine, what is to live? The conjunction of these terms points to a proletarian idealism. How else would their author have thought of his age, of life, but ideally? He who had worked with Behrens, Gropius, and, barely thirty when at war’s end, painted — and wrote, with Ozenfant, Apres le Cubisme.

Life, work, art. So youthful, so noble, so pure.

So passing.

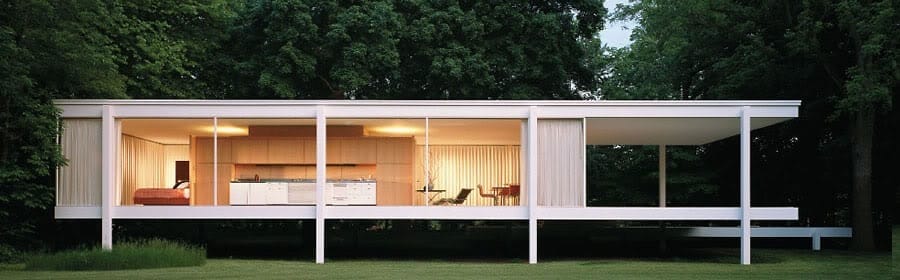

I would like to think there is another version of this aphorism: the house is a machine which is living. Only vivifying it presents a difficulty. What could it mean? One suspects Mies: guilt by association (the two, he and Corbu, being often conjoined in the literature). But time had moved on, and to a place far from Berlin. The machine had become no longer an abstraction, but a consumer product. And here was Mies with his glass-box house to put a Mrs Farnsworth in as some sort of living female sculpture. [1] Which is strange, unless we interpret “living machine” in some metaphysical sense. Mrs Farnsworth may really have been the house. And that would not be pushing it since, a century having passed, the coupling of Mies’s purpose with his client’s obsession doesn’t seem so unnatural; or since, when we stare at her name in a book, the realisation that her fame lives after her doesn’t seem so surprising. Mrs Farnsworth. Immortalised by Mies. The sculptural thing almost passes for a female metaphor, as the glass-box does for some incarnate machine. If not quite. For having exhausted the possibilities of these metaphors the phrase remains, still an enigma.

Except that we’re dealing with two different eras. That is the clue to the puzzle. It tells us that through Le Corbusier, through Mies van der Rohe (their names are symbols), architecture, or really art, spans the generations, one to the next. The first in this case is the twenties, the age of machine utopia and of the artistic manifesto — futurism, cubism, constructivism. The ethos of that age was naive and earnest, but its ironic sadness has endured, if only as a worker wound through the giant cogs of a machine. [2] It was this naive synthesis of technical and social promise that partly motivated those youthful intentions to reconstruct a destructed world from its basic elements and all the symbols of a new functionalism.

The second era is, by inference, our own, and is ongoing. The dom-ino house only exists, really, in the mind. It would morph, eventually, into a Gehry CAD drawing. It is still morphing. The “house” has become a total chameleon, a “machine”, a creation as insubstantial as can be made by the time in which we live.

But living? Yes, if we imagine the dwelling as an ever-changing thing, an endlessly self-replicating series. Whether as marks on paper of an ancient dreamer, an urbanscape of sculptures cheek by jowl, or a megalith, it hardly matters. And whether the cell of a lonely individual, or a hive seething with life, that too does not negate its essential purpose.

Notes:

[1] Singley, P (1994), Living in a glass prism: the female figure in Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s domestic architecture, in Transitions Journal, issue 44/45, pp 20-31

[2] Chaplin’s Modern Times.